She built one of the most striking homes on the Hudson River — and the nation’s first female self-made millionaire managed it all on her own, giving back generously along the way.

Madam C.J. Walker was born Sarah Breedlove in 1867. Her parents, Owen and Minerva, were Louisiana sharecroppers who had earlier been enslaved. She was their fifth child, yet the first born directly into freedom after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued.

Walker’s early life was traumatic, as the numbers show: Her parents both died by the time she was seven. She was married by 14, a mother at 17, and a widow at 20. With a daughter, A’Lelia, to support on her own, she was determined to do better.

Walker moved to St. Louis, where she washed clothes for $1.50 per day. There she also met her future husband, Charles J. Walker, whose name would inspire her empire. After losing part of her hair to scalp disease, she came up with a formula for a hair-care system that involved preparing the scalp with lotions and pomades.

She launched her business with just over $1 in capital. Summoning her powerful entrepreneurial instincts, Walker continued moving for opportunity — from Denver to Pittsburgh to Indianapolis, which had a prosperous Black business community. Eventually she employed thousands. Many of them were Black saleswomen who found their own economic success through her company.

Within a dozen years, she’d gone from washerwoman to millionaire. Charles J. Walker helped with aspects of the business like mail orders and advertising early on, but eventually the couple drifted apart and divorced.

By this time Walker was so successful she had a presence in New York City, but she also wanted a country home. The showplace she built, Villa Lewaro in Irvington, was designed by noted Black architect Vertner Tandy. It stood not far from the estates of John D. Rockefeller and Jay Gould.

Villa Lewaro became a gathering place for Harlem Renaissance intellectuals, including Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, and W. E. B. Du Bois. Walker’s daughter, A’Lelia Walker, became a significant figure in the movement in her own right.

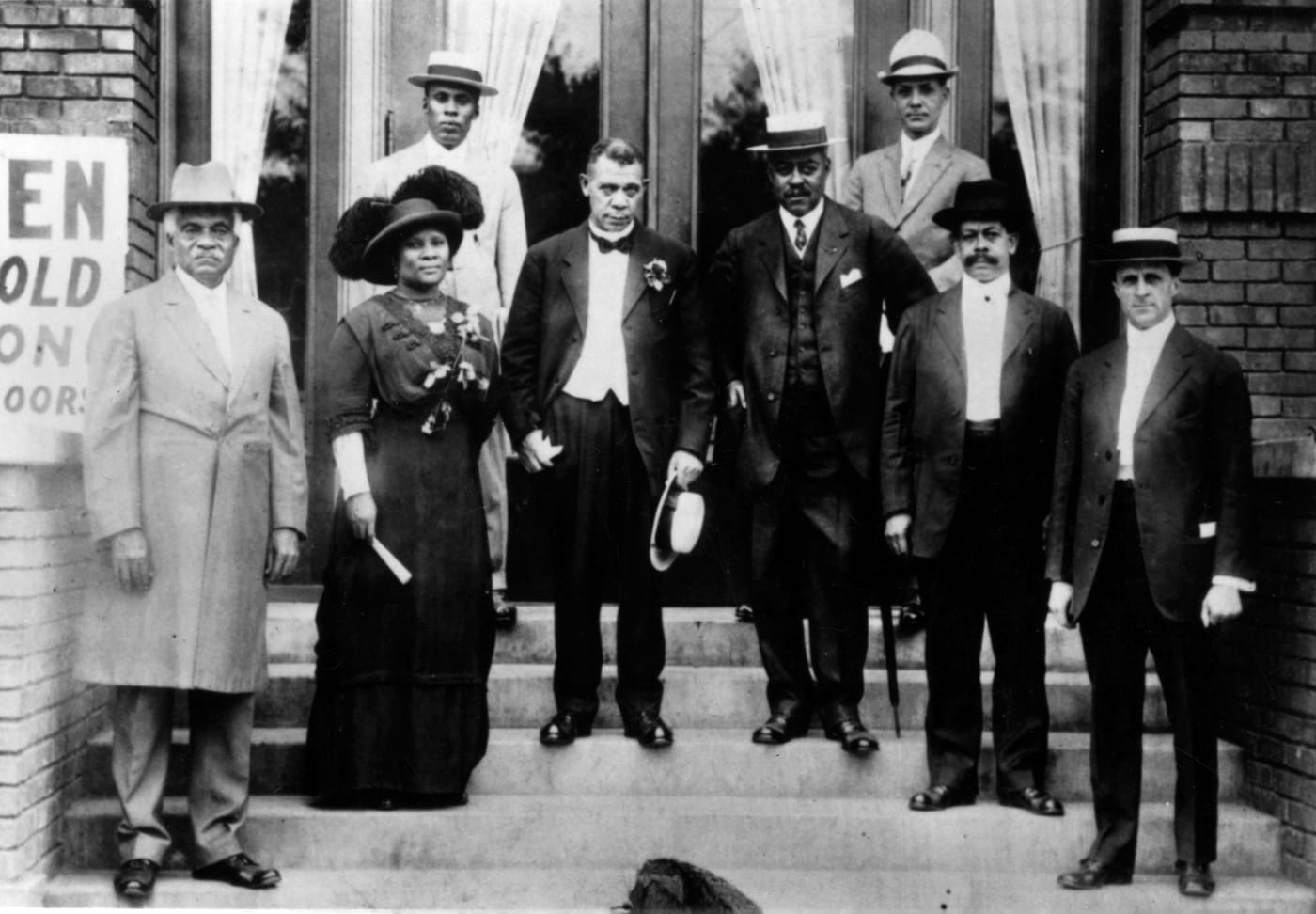

Madam Walker herself was a generous donor, especially to causes advancing the Black community. She gave scholarships to women at the Tuskegee Institute and significant funding to the anti-lynching campaign of the NAACP, among other institutions.

Helena Doley, a later owner of Villa Lewaro, has described the home as part of a communal legacy. “Madam didn’t build this house because she had an ego … or to say, ‘Here I am, a grand lady. Look what I have done,'” Doley told the National Trust for Historic Preservation. “She built it as an inspiration for a people, for a community, for all of us of any color, to see what could be done. What could be done with tenacity, with perseverance, with just dogged determination.”

Walker acknowledged that her success had come with huge effort. “If I accomplished anything in life it is because I have been willing to work hard,” Walker told the New York Times. “I have never yet started anything doubtingly, and I have always believed in keeping at things with a vim.”

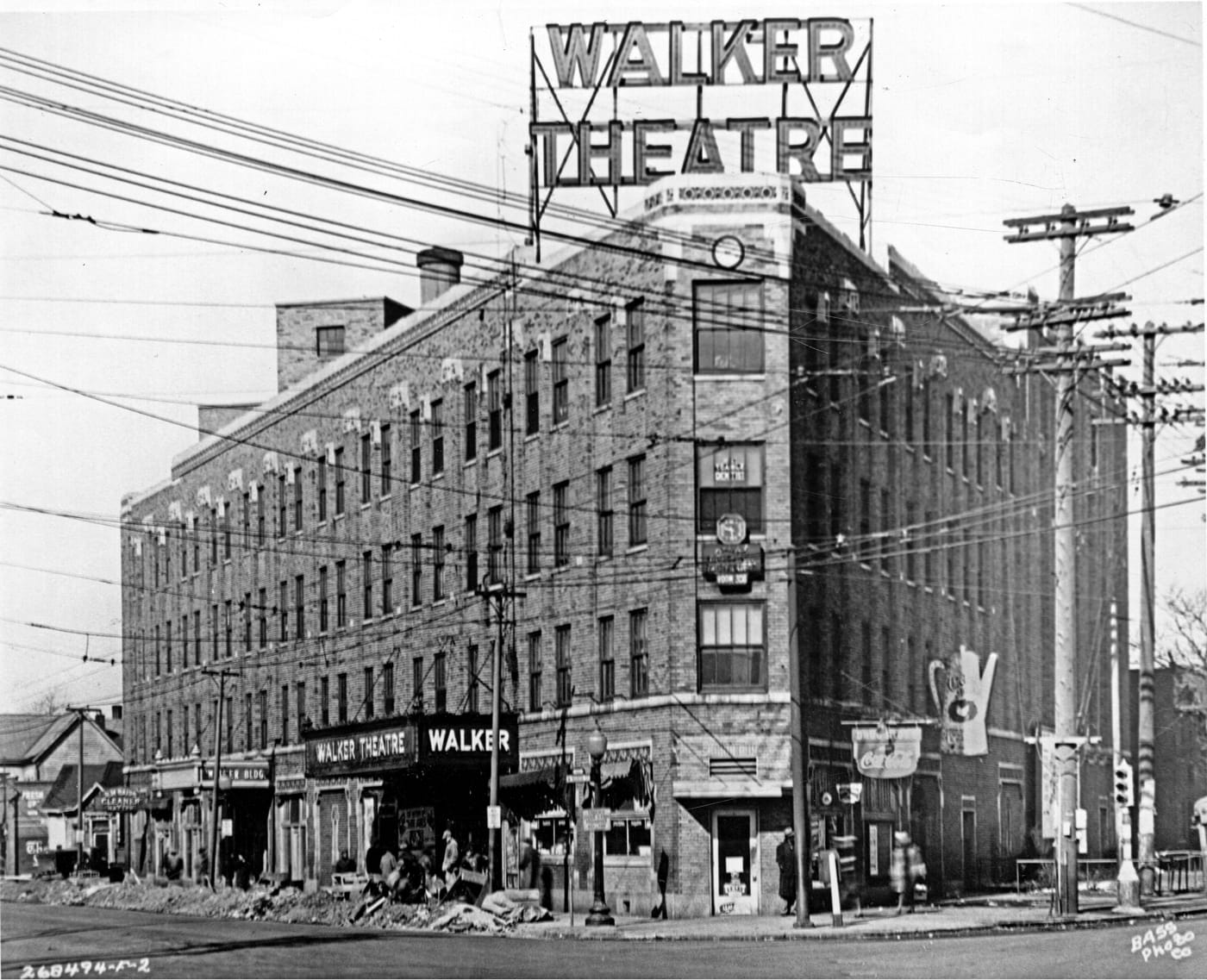

The Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company headquarters and Walker Theatre in 1930. (Photo: Courtesy the Indiana Historical Society)

Walker died in 1919. Yet in recent years, a century after she shattered barriers, Walker has been freshly celebrated. On Her Own Ground, a biography by her great-great-granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, became a bestseller in 2001.

In 2020, Oscar winner Octavia Spencer starred as Walker in the four-part Netflix series “Self Made.” And last year — fittingly for an entrepreneur who shared her success from the beauty and hygiene industry — Mattel released a Barbie doll of Walker as part of its Inspiring Women series.