A little-known incident that took place in Troy illustrates the fearlessness of Harriet Tubman, the renowned abolitionist and rescuer of enslaved people. During an 1860 stopover in the city, she risked her own life to free Charles Nalle, who had escaped enslavement but was in custody and awaiting return to to the South. This excerpt about the event comes from Harriet: Moses of Her People, written by Sarah H. Bradford in 1886, during Tubman’s lifetime:

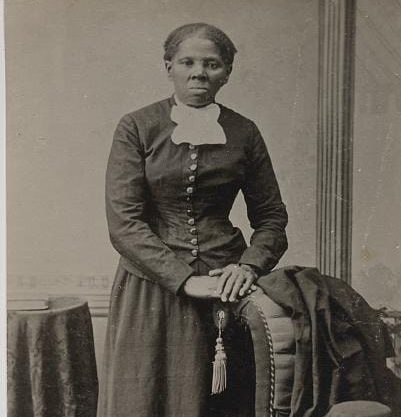

– Library of Congress photo

Harriet Tubman was requested by [abolitionist] Mr. Gerrit Smith to go to Boston to attend a large anti-slavery meeting. On her way, she stopped at Troy to visit a cousin, and while there the people were one day startled with the intelligence that a fugitive slave was already in the hands of the officers, and was to be taken back to the South. The instant Harriet heard the news, she started for the office of the United States Commissioner, scattering the tidings as she went.

An excited crowd was gathered about the office, through which Harriet forced her way, and rushed up stairs to the door of the room where the fugitive was detained. A wagon was already waiting before the door to carry off the man, but the crowd was even then so great, and in such a state of excitement, that the officers did not dare to bring the man down. Time passed on, and he did not appear. “They’ve taken him out another way, depend upon that,” said some of the people. “No,” replied others, “there stands ‘Moses’ yet, and as long as she is there, he is safe.”

Harriet, now seeing the necessity for a tremendous effort for his rescue, sent out some little boys to cry fire. The bells rang, the crowd increased, till the whole street was a dense mass of people. Again and again the officers came out to try and clear the stairs; others were driven down, but Harriet stood her ground. “Come, old woman, you must get out of this,” said one of the officers; “If you can’t get down alone, someone will help you.”

Harriet, still putting on a greater appearance of decrepitude, twitched away from him, and kept her place. At length the officers appeared and announced to the crowd, that if they would open a lane to the wagon, they would promise to bring the man down the front way.

The lane was opened, and the man was brought out with his wrists manacled together, walking between the U.S. Marshall and another officer. The moment they appeared, Harriet roused from her stooping posture, threw up a window, and cried to her friends: “Here he comes—take him!” and then darted down the stairs like a wild-cat. She seized one officer and pulled him down, then another, and tore him away from the man; and keeping her arms about the slave, she cried to her friends: “Drag us out! Drag him to the river.”

Again and again they were knocked down, the poor slave utterly helpless, with his manacled wrists, streaming with blood. Harriet’s outer clothes were torn from her, yet she never relinquished her hold of the man, till she had dragged him to the river, where he was tumbled into a boat.

P.S. Despite Tubman’s heroics, Nalle soon was recaptured. Eventually, local abolitionists collected $650 — about $20,000 today — to secure his freedom. A plaque at the corner of State and 1st streets in Troy, near where the incident occurred, recognizes the event.

Born in 1821, Nalle had fled the Virginia plantation where he was enslaved in 1858, after hearing news that he probably would be auctioned off soon, and most likely wind up on a plantation in the deep South. Ironically, Nalle was the son of a white Virginia planter and an enslaved woman who was herself half white. He made his escape while visiting his wife, Kitty, who had been freed and lived with their children in Washington, D.C. He died there in 1875.