Nobody can resist a good ghost story. That may be why the TV show “Ghosts,” set in the Hudson Valley, has such a devoted following. Our region has contributed its own share of spine-tingling tales. The ones that have stood the test of time — scaring people for generations — can be traced to long-ago tales of mystery or tragedy. In fact, they provide a compelling way of keeping the past alive.

Scenic Hudson asked three experts on the region’s supernatural tales — an academic who has researched them, a master storyteller, and a folklorist — to share (and in one case tell) their favorite Hudson Valley ghost stories and what about them continues to thrill and chill.

The Servant Girl of Leeds:

Favorite of Judith Richardson

One Hudson Valley ghost tale that I am endlessly drawn to concerns a ghostly servant girl who haunts Leeds, in Greene County. The basic story goes like this: Sometime in the mid-18th century, a servant girl ran away from the house of her master, a wealthy and prominent man. The master chased after her, caught her, and tied her to his horse. The horse then bolted (whether by tragic accident or by deliberate provocation continues to be an object of debate through various retellings), and the poor girl was gruesomely dashed to death.

Although some versions of the story hold that the master was sentenced to wear a noose around his neck for the remainder of his years, it seems he escaped any real prosecution or punishment. However, if the courts failed to do justice, then the spirit world, with the help of human storytellers, had something else to say. Reports soon emerged that on any given night, if one passed the fatal spot — variously known as Spooky Hollow or Spook Rock — one might confront a host of specters, including, of course, the ghost of a woman being dragged by a spectral horse. And these stories continue to be told into the present day.

What makes this story so compelling to me is that, at some level, it is true, and true to place. There really was a servant girl — named Anna Dorothea Swarts — who died in this way in this place in 1755. Her master, William Salisbury, really was one of the richest men in the region. And although a bill of indictment was drawn up (strangely some seven years after the fact), it was officially “ignored.” The initial story thus seems to emerge from a simmering sense of injustice in the local community regarding the original case, and with this reflects particular historical conditions and local conflicts, including class tensions and the existence of exploitative systems of servitude (including slavery) in the Hudson Valley. Where other stories may be generic, transplanted, even fabricated, this story is authentically rooted in this locality — its history, community, and culture — in unique and abiding ways.

But what also fascinates me about this story is its shiftiness. As the story of the servant girl’s ghost has been told and retold over the centuries, it has gone through any number of variations, particularly in terms of the servant girl’s identity. Depending on who you talk to, or on what version you read, the girl in question can switch from Scottish to Native American, from German (and hence linked to Hessians in the American Revolution) to Spanish.

What emerges in these mutations is something about the workings of ghost stories, and ghostliness itself. There is a malleability to tales of haunting … that invites our participation and interpretation. If at one level ghost stories are about the past … then they are also about the present. They offer an uncanny mirror of each generation’s, and each teller’s, contexts, conflict, fears, and desires. This double-edged relationship to vestige and novelty, to powerlessness and presence, is why Anna Dorothea Swarts’s ghost continues to haunt Leeds — why she continues to haunt me. The main work of haunting is done by the living.

A Hudson Valley native, Judith Richardson teaches in the English Department at Stanford University in California, and is coordinator of its American Studies Program. She is the author of Possessions: The History and Uses of Haunting in the Hudson Valley, and has published essays on Washington Irving, James Fenimore Cooper, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and other topics in American literature and culture. She currently is at work on a book about 19th-century America’s “plantmindedness,” its obsession with vegetable matters.

The Imps of Donderberg:

Favorite of Jonathan Kruk

“In the bosom of one of those spacious coves which indent the eastern shore of the Hudson, at that broad expansion of the river denominated by the ancient Dutch navigators the Tappan Zee, and where they always prudently shortened sail, and implored the protection of St. Nicholas when they crossed…”

Why does Washington Irving start “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” with this spirited warning for skippers? Legend has it that the Imps of Donderberg haunt all sailors daring to enter the treacherous Hudson Highlands. These ghosts of those who drowned send storms to wreak havoc upon ships failing to acknowledge the mysterious powers of the river. As a storyteller, I love sharing the spirit/fairie nature of these mischief-makers.

Listen to Jonathan Kruk tell the story in the audio file below, or watch him on CBS’ Sunday Morning.

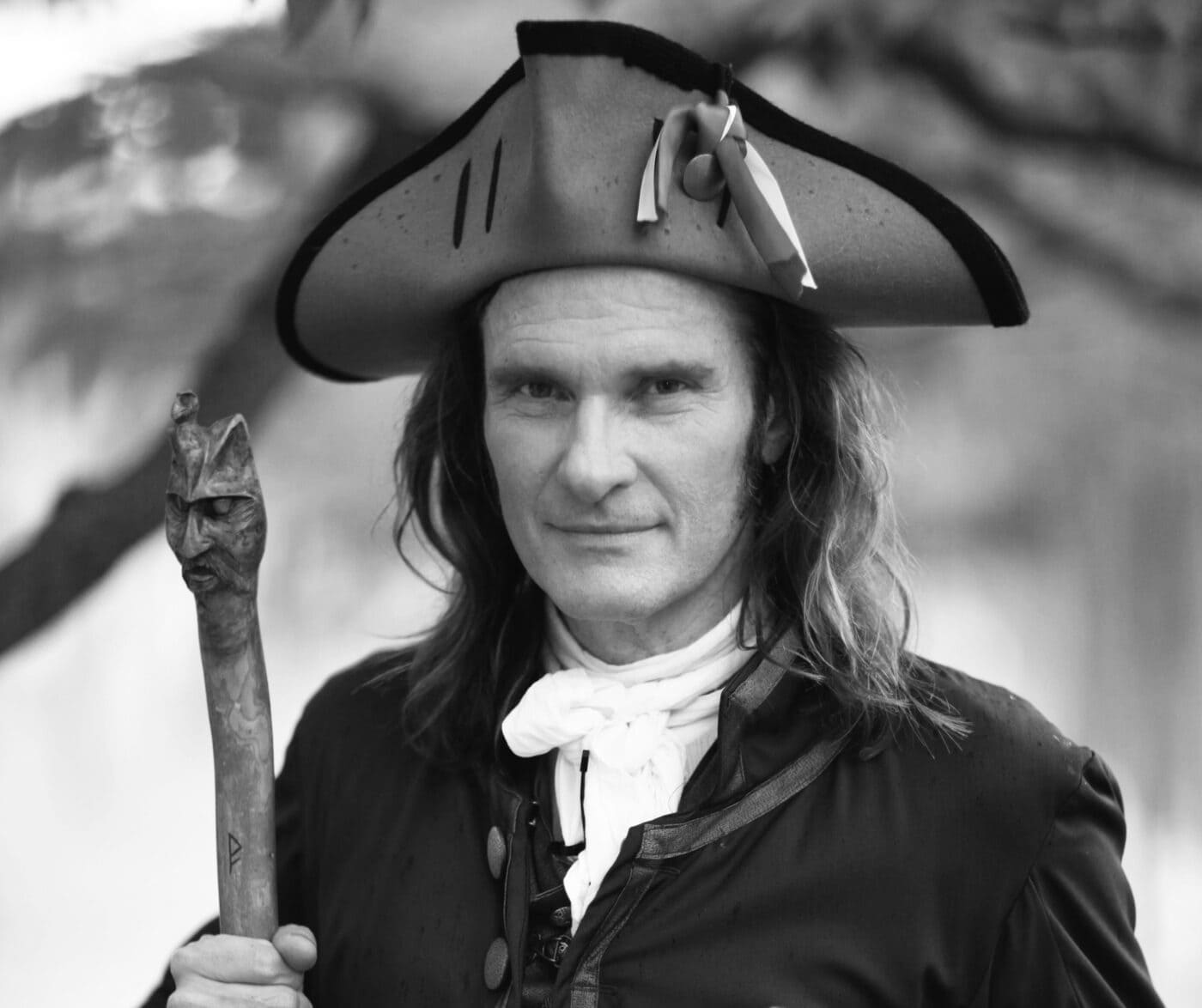

Since 1989, award-winning storyteller Jonathan Kruk has been enchanting children and adults alike with riveting tales of the region, encouraging them to listen, learn, and imagine. Renowned for his solo presentation of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” Kruk engages audiences at schools, libraries, historic sites, museums, and summer camps. He’s also the author of two books, Legends and Lore of the Hudson Highlands and Legends and Lore of Sleepy Hollow and the Hudson Valley.

Ghostly Legends of Captain Kidd:

Favorite of Ellen McHale

Legends are tales that contain a kernel of some historical truth, whether because of the existence of a person or event on which they are based. Legends also often exist in cycles. The notorious pirate Captain Kidd (William Kidd, c. 1655-1701) is one such person whose exploits and tales of treasure have existed in multiple forms. I am intrigued by this cycle because of the variety of tales and their ties to New York State.

According to the legend cycle, Captain Kidd is said to have buried his treasure in locations between the coast of Maine and the Florida Keys, including places along the Hudson River. One legend was documented in The WPA Guide to New York, first published during the Great Depression as part of the Federal Writers Project. In this story, “Kidd’s Plug” — a craggy portion of the Hudson shoreline near West Point – is said to contain a cavern, concealed by a rock, where the pirate cached some of his gold.

In his Myths and Legends of Our Own Land (1896), Charles M. Skinner adds intriguing details about the rock: “Though it is 200 feet up the cliff, inaccessible either from above or below, and weighs many tons, still, as pirates and devils have always been friendly, it may be that the corking of the cave was accomplished with supernatural help, and that if blasts or prayers ever shake the stone from its place a shower of doubloons and diamonds may come rattling after it.”

In many tales, Captain Kidd — who was executed for murder and piracy — is the ghostly protector of his treasure. When two soldiers commenced digging at one purported hiding place along the Hudson in 1825, the story goes that a menacing figure rose from the ground and caused the men to faint. Both swore it was the specter of Kidd, keeping watch over his loot.

Public folklorist Ellen McHale has served since 1999 as executive director of the non-profit New York Folklore, dedicated to supporting folk arts and folk culture in New York through advocacy, education, support for folk artists and practitioners, and public outreach. Since 1945, the Schenectady-based organization has published Voices: The Journal of New York Folklore, a benefit of membership.

Take a walk on the spooky side by attending Historic Hudson Valley’s Great Jack O’Lantern Blaze, one of the region’s great fall traditions, which continues in Croton-on-Hudson through Nov. 21.