Editor’s Note: This article contains mentions of slavery that, while not graphic, may be disturbing.

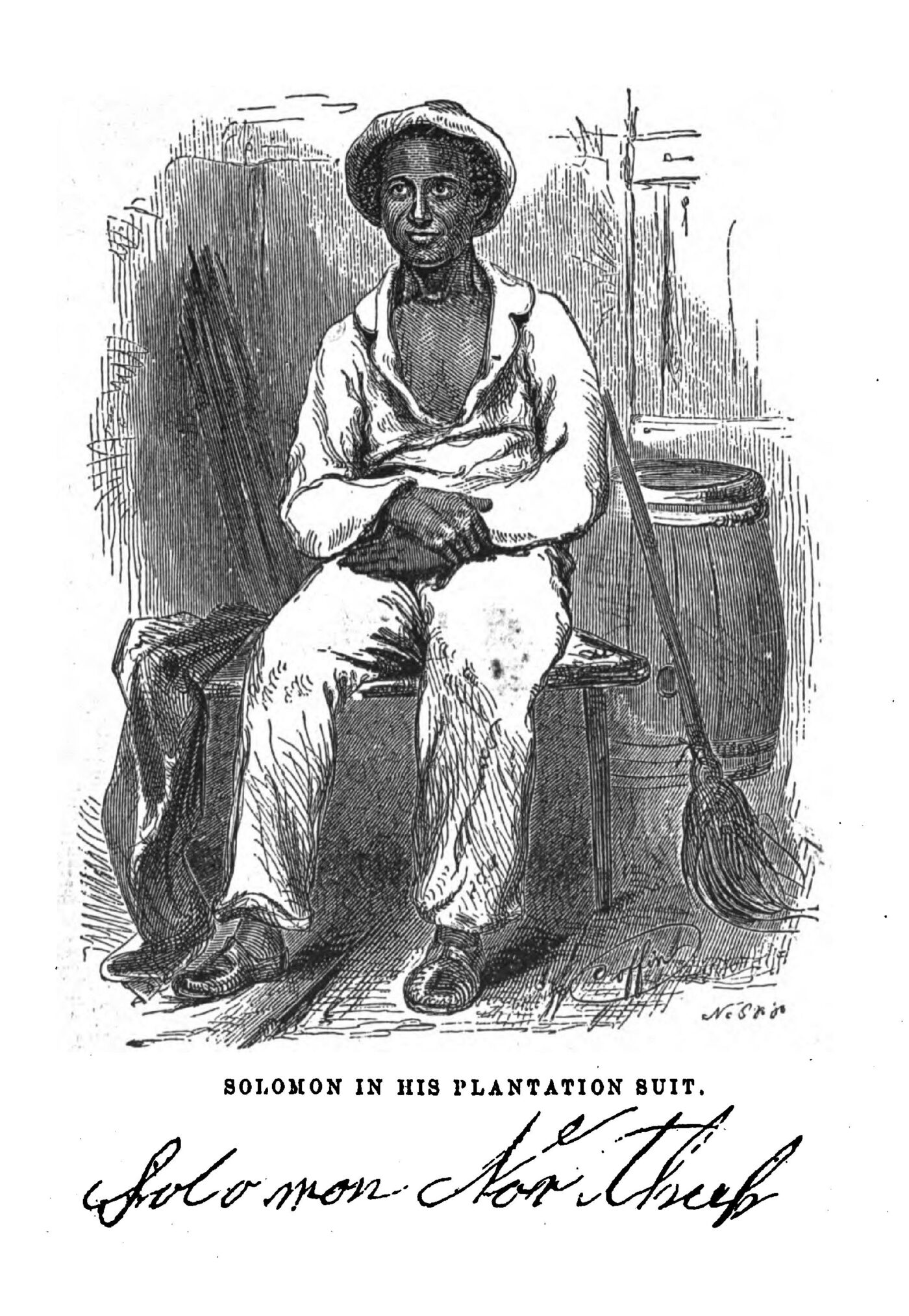

Few could describe the horrors of enslavement more vividly than Solomon Northup, author of Twelve Years a Slave. Published in 1853, the year Northup secured his freedom, the book became an immediate bestseller. Northup brought the fear and terror experienced daily by enslaved people into the homes — and hearts — of those, Northern and Southern alike, who had conveniently overlooked the ordeal of their fellow Americans. Northup’s personal story inspired millions, as he maintained his mind, body, and spirit while in bondage, and ultimately was joyfully reunited with his family in New York.

Even those who’ve read the book may not realize that Northup came from the upper Hudson Valley. Born free in the foothills of the Adirondacks, he lived in Washington and Saratoga counties with his wife Anne and their children.

Northup worked as a laborer, carriage driver, and fiddler before being duped to travel to Washington, D.C., supposedly to play his violin in a circus. He was sold instead to a slave trader. Northup spent the next dozen years on Louisiana plantations before his freedom was secured and he reconnected with his family.

The story received fresh attention a decade ago, when it was made into a major 2013 film. “12 Years a Slave” won the Academy Award for Best Picture — the first for a movie made by a Black director in Oscar history.

Today Saratoga Springs has placed a plaque honoring Northup’s roots there, and local activist Renee Moore founded the annual Solomon Northup Day commemoration in 1999. “We needed to bring the focus back to a community that has been here for generations but is often invisible,” Moore says.

Solomon Northup Day was later organized by Skidmore College, and as Northup’s story has become better known, many of his descendants have attended, along with notables like Oscar-winning actress Lupita Nyong’o. The annual event is now hosted by the North Country Underground Railroad Association.

“My hope for Solomon Northup Day is that it continue to inspire young people and the entire community, realizing their common history, so that we can work together to create a more perfect union,” Moore says.

Whether you’ve seen the movie or never heard the story, here are questions modern readers might ask about Northup’s experience under slavery — answered directly in excerpts from the book.

What was Northup’s daily life with Anne like before enslavement?

“We were the parents of three children — Elizabeth, Margaret, and Alonzo. They filled our house with gladness. Their young voices were music in our ears. Many an airy castle did their mother and myself build for the little innocents. When not at labor I was always walking with them, clad in their best attire, through the streets of Saratoga. Their presence was my delight.”

“The history of my life presents nothing whatever unusual — nothing but the common hopes, and loves, and labors of an obscure colored man, making his humble progress in the world.”

How did he find himself enslaved?

“I was told that it was necessary to go to a physician and procure medicine. Going towards the light, which I imagined proceeded from a physician’s office, is the last glimmering recollection I can recall. From that moment I was insensible. How long I remained in that condition — whether only at night, or how many days and nights — I do not know; but when consciousness returned, I found myself alone, in utter darkness, and in chains.”

How did he cope?

“Had it not been for my beloved violin, I scarcely can conceive how I could have endured the long years of bondage. It introduced me to great houses — relieved me of many days’ labor in the field — supplied me with conveniences for my cabin — with pipes and tobacco, and extra pairs of shoes, and oftentimes led me away from the presence of a hard master, to witness scenes of jollity and mirth. It was my companion — the friend of my bosom — triumphing loudly when I was joyful, and uttering its soft, melodious consolations when I was sad.”

What happened after a letter Northup wrote about his plight finally reached Saratoga, and an acquaintance journeyed south to find him?

“He came toward me across the cotton field. A world of images thronged my brain; a multitude of well-known faces — Anne’s, and the dear children’s, and my old dead father’s; all the scenes and associations of childhood and youth; all the friends of other and happier days, appeared and disappeared, flitting and floating like dissolving shadows before the vision of my imagination, until at last the perfect memory of the man recurred to me, and throwing up my hands towards Heaven, I exclaimed, in a voice louder than I could utter in a less exciting moment — “Thank God — thank God!”

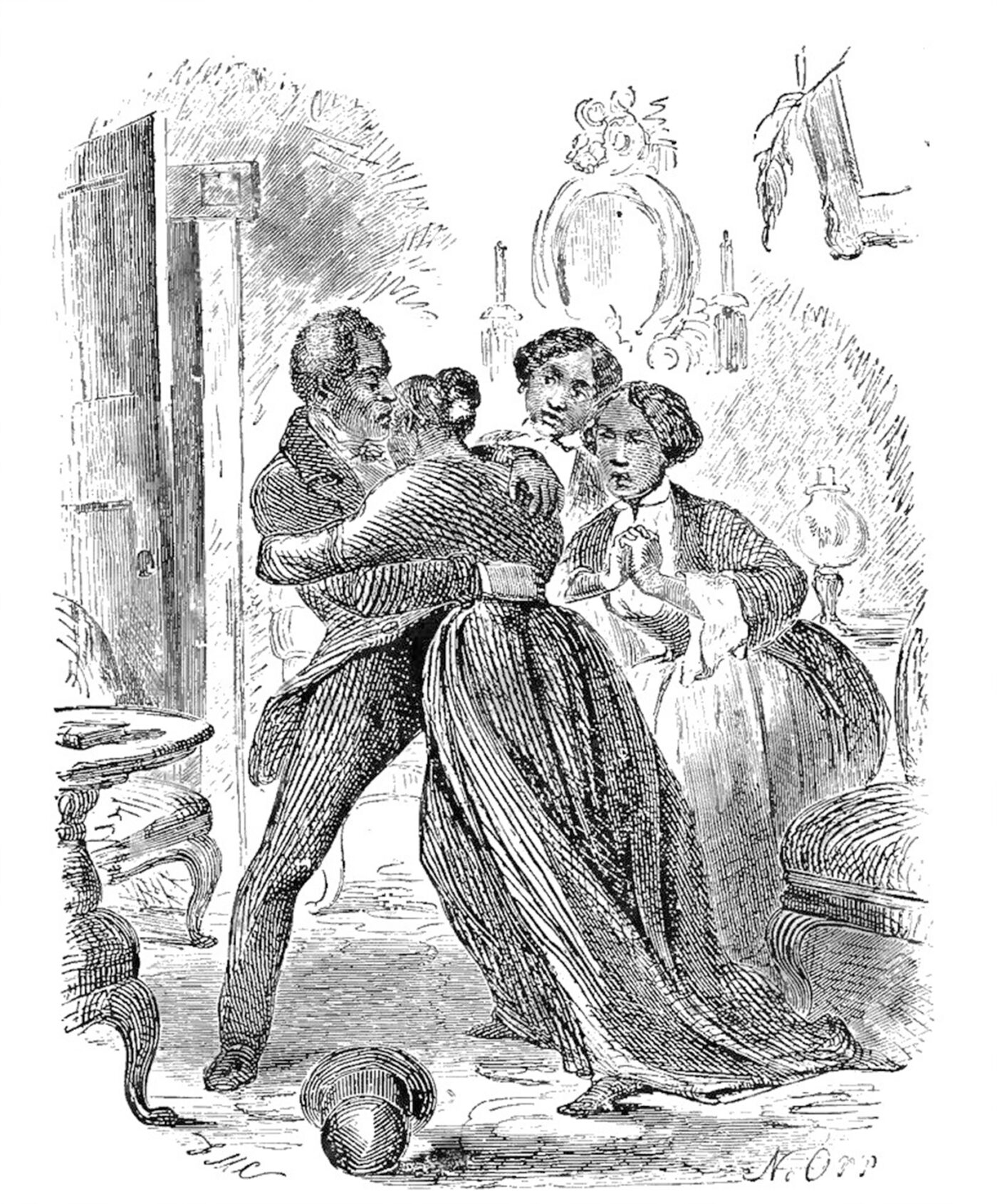

Was Northup reunited with his family?

“We left Washington on the 20th of January, proceeding by the way of Philadelphia, New-York, and Albany. The following morning I started … for Glens Falls, the residence of Anne and our children. As I entered their comfortable cottage, Margaret was the first that met me. She did not recognize me. When I left her, she was but seven years old, a little prattling girl, playing with her toys. Now she was grown to womanhood—was married, with a bright-eyed boy standing by her side. Not forgetful of his enslaved, unfortunate grand-father, she had named the child Solomon Northup Staunton. When told who I was, she was overcome with emotion, and unable to speak. Presently Elizabeth entered the room, and Anne came running from the hotel, having been informed of my arrival. They embraced me, and with tears flowing down their cheeks, hung upon my neck. But I draw a veil over a scene which can better be imagined than described.”