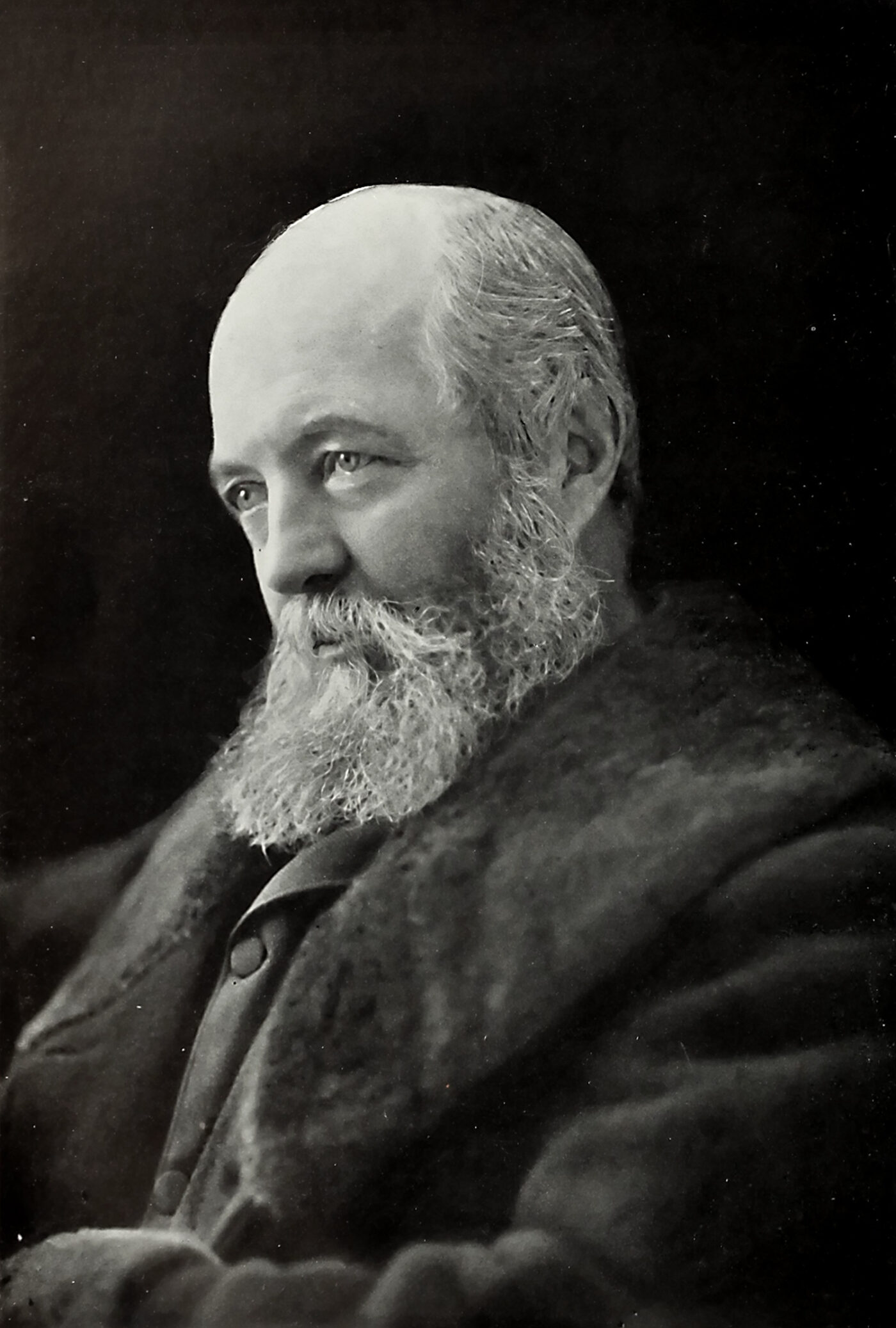

Farmer, merchant, seaman, journalist — nothing on Frederick Law Olmsted’s résumé before 1857, when he turned 35, even hinted that he would become America’s foremost landscape architect. Yet throughout 2022, to mark the bicentennial of Olmsted’s birth on April 26, people will gather in parks he designed all across the country — including Downing Park in Newburgh — to celebrate his remarkable vision for making nature accessible to everyone.

Olmsted’s start in landscape architecture — a term he coined with his longtime business partner, Calvert Vaux — began when he successfully applied to be superintendent of Manhattan’s Central Park. At that point, there was no park, and no plans had been approved. Andrew Jackson Downing, considered the “father” of American landscape design, suggested that Olmsted and Vaux (who had worked for Downing) throw their hats in the ring.

Dreaming up the ideal park

Olmsted may have been a newbie to park planning, but he recognized the potential of open space to enrich people’s lives. Growing up in Hartford, Conn., he frequently accompanied his father on trips through New England and New York in search of places that fit the “picturesque” ideal — the 19th-century Romantic notion that landscapes can nurture people both physically and spiritually. Later, he traveled to Europe, spending much of his time walking through parks and private estates.

Olmsted became convinced that all Americans deserved close-to-home landscapes where they could go for a dose of nature’s healing and restorative powers. In the mid-19th century, such places were few and far between. “The enjoyment of the choicest natural scenes in the country and the means of recreation connected with them is thus a monopoly…of a very few very rich people,” he wrote. “The great mass of society, including those to whom it would be of the greatest benefit, is excluded from it.”

With Central Park, as beautiful as any private estate, Olmsted and Vaux virtually opened the door to the natural world. Its curving pathways, mix of meadows and woods, lakes and streams, closed-in spaces and long-range vistas in the heart of the metropolis set the standard for parks — both in terms of its naturalistic design and inclusivity — then and now.

Open spaces like Central Park and the hundreds of others Olmsted created, including Brooklyn’s Prospect Park and entire park systems in Buffalo, Boston, and Louisville, fulfilled his goals: “We want a ground to which people may easily go when the day’s work is done, and where they may stroll for an hour, seeing, hearing, and feeling nothing of the bustle and jar of the streets where they shall, in effect, find the city put far away from them.”

Olmsted’s greatness in planning parks came from his excellent eye, his ability to take stock of a specific landscape, and his intuitive understanding of how to maximize enjoyment. As famed Chicago architect Daniel Burnham said of him, “He paints with lakes and wooded slopes; with lawns and banks and forest-covered hills; with mountainsides and ocean views.” The title of a 2011 biography of Olmsted summarizes his talent: Genius of Place.

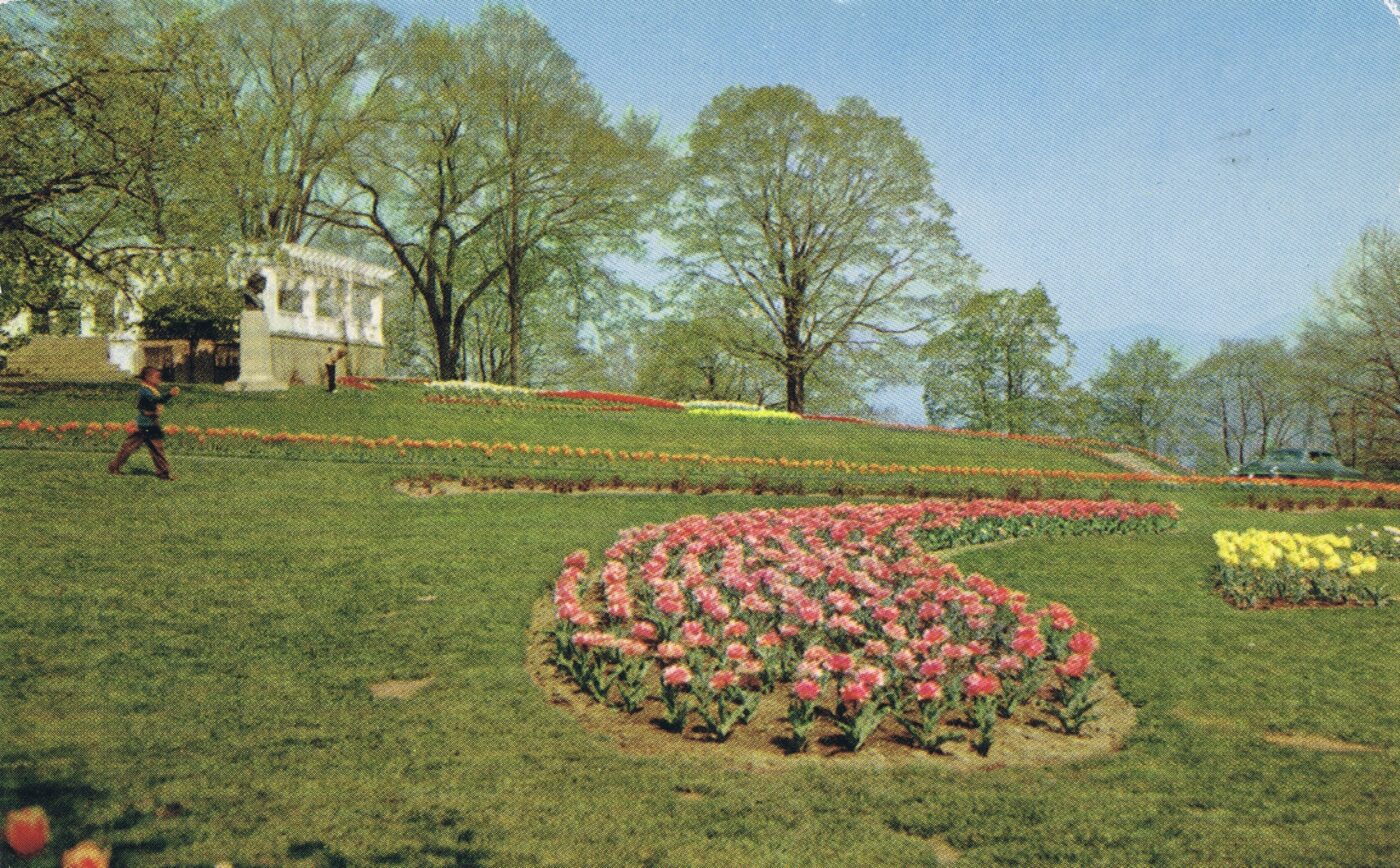

Bringing lessons learned to the valley: Downing Park

Olmsted brought everything he’d learned to bear in Newburgh’s 35-acre Downing Park — especially what landscape architects call “circulation,” a sense of continual discovery. Walking through it, the visitor enjoys changing, often surprising, views of its varied natural features — a hill offering Hudson River views, dramatic rock outcroppings, stately trees, and a placid pond.

Downing Park has a special place in the Downing-Vaux body of work. It was the last project they worked on together (Vaux died three years before the park’s opening in 1897), and it commemorated Downing, who died in a steamboat accident on the Hudson River in 1852. Olmsted and Vaux agreed to provide a design for the park for free if it were named after their mentor, who had lived in Newburgh.

At first, the park was envisioned to encompass only its hilly eastern section (originally crowned with an observation tower that became a destination for visitors arriving by Hudson River Dayliners). However, Olmsted persuaded the city to add the adjacent flat acreage to the west, allowing creation of Polly Pond (named after polliwogs) and grassy meadows for family picnics and larger community events. (Interestingly, a similar Olmsted-Vaux creation, the Great Lawn at the former Hudson River Psychiatric Hospital in Poughkeepsie, is being restored as part of the new Hudson Heritage development.)

As City of Newburgh historian Mary McTamaney notes, Downing Park is itself a “central park,” located in the middle of the city. In creating this green space, Olmsted and Vaux followed through on instructions to provide a place that would meet residents’ needs for recreation and a boost to the spirit — what the park commissioners called the “unbending of one’s faculties.”

“The city fathers had said to them, ‘We want a passive park for decompressing.’ You have to remember this was an industrial town and people had a hard time, working in the factories six days a week,” explains McTamaney.

McTamaney grew up near Downing Park, and it became her outdoor haven from an early age. “I have photos of me being pushed through it in a wicker stroller,” she recalls. Later, she enjoyed more active pursuits there. “You weren’t allowed to be loud and wild, but we’d run up and down the hills. In the winter we’d go sledding. It’s where you’d learn to ride your bike. And it was always the backdrop for family photos. It was just a fresh air sanctuary, and so beautiful.”

And that’s what it remains, says Kathy Parisi, president of the Downing Park Planning Committee, the volunteer group responsible for the park’s upkeep and ongoing restoration. “There are a lot of people who walk or jog there every day. And I can’t tell you how many groups want to have events in the park,” everything from gospel choirs to Tai Chi workshops.

While all of Olmsted’s parks have undergone changes, their creator’s original vision remains intact, and so does his influence over succeeding generations of landscape designers, including Kim Mathews, who oversaw the plans for Scenic Hudson’s West Point Foundry Preserve while a founding principal at Mathews Nielsen Landscape Architects.

“Frederick Law Olmsted’s landscape plans grew from personal observation and the qualities of a particular place. He was committed to the restorative value of landscapes — a theme that still resonates in society today. His design legacy, his commitment to working within the public realm, and the extraordinary way he revealed a place through circulation were all early inspirations in my own design career,” she says.

To the benefit of all, the legacy of this “Genius of Place” lives on.

The Downing Park Planning Committee and Garden Club of Orange and Dutchess Counties are co-hosting a celebration of Olmsted’s life and legacy at Downing Park on Saturday, April 23, beginning at 2 p.m. Titled “Parks for all People,” the free event will include remarks by Anne Petri, past president of the Garden Club of America and current president and CEO of the National Association of Olmsted Parks, and a tree planting by students from local schools.